The typical strategy when treating microbial infections is to blast the pathogen with an antibiotic drug, which works by getting inside the harmful cell and killing it. This is not as easy as it sounds, because any new antibiotic needs to be both water soluble, so that it can travel easily through the bloodstream, and oily, in order to cross the pathogenic cell’s first line of defense, the cellular membrane. Water and oil, of course, don’t mix, and it’s difficult to design a drug that has enough of both characteristics to be effective.

The difficulty doesn’t stop there, either, because pathogenic cells have developed something called an “efflux pump,” that can recognize antibiotics and then safely excrete them from the cell, where they can’t do any harm. If the antibiotic can’t overcome the efflux pump and kill the cell, then the pathogen “remembers” what that specific antibiotic looks like and develops additional efflux pumps to efficiently handle it—in effect, becoming resistant to that particular antibiotic.

One path forward is to find a new antibiotic, or combinations of them, and try to stay one step ahead of the superbugs.

“Or, we can shift our strategy,” says Alejandro Heuck, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at UMass Amherst and the paper’s senior author.

[…]

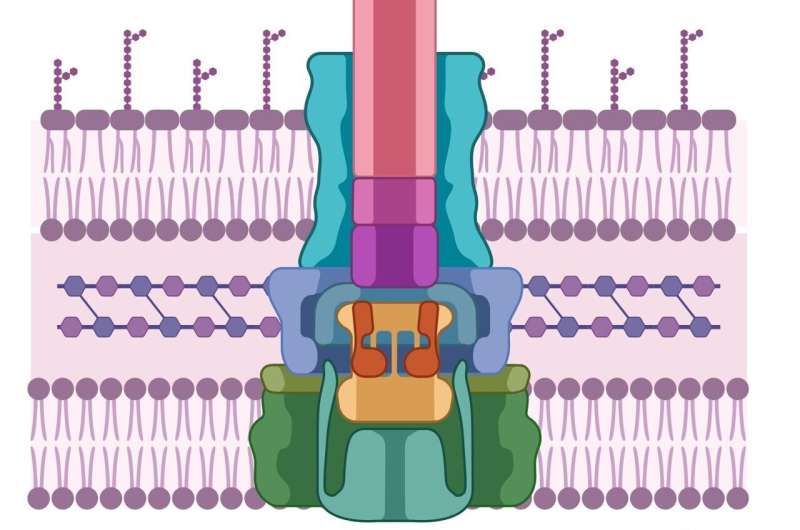

Like the pathogenic cell, host cells also have thick, difficult-to-penetrate cell walls. In order to breach them, pathogens have developed a syringe-like machine that first secretes two proteins, known as PopD and PopB. Neither PopD nor PopB individually can breach the cell wall, but the two proteins together can create a “translocon”—the cellular equivalent of a tunnel through the cell membrane. Once the tunnel is established, the pathogenic cell can inject other proteins that do the work of infecting the host.

This entire process is called the Type 3 secretion system—and none of it works without both PopB and PopD. “If we don’t try to kill the pathogen,” says Heuck, “then there’s no chance for it to develop resistance. We’re just sabotaging its machine. The pathogen is still alive; it’s just ineffective, and the host has time to use its natural defenses to get rid of the pathogen.”

[..]

Heuck and his colleagues realized that an enzyme class called the luciferases—similar to the ones that cause lightning bugs to glow at night—could be used as a tracer. They split the enzyme into two halves. One half went into the PopD/PopB proteins, and the other half was engineered into a host cell.

These engineered proteins and hosts can be flooded with different chemical compounds. If the host cell suddenly lights up, that means that PopD/PopB successfully breached the cellular wall, reuniting the two halves of the luciferase, causing them to glow. But if the cells stay dark? “Then we know which molecules break the translocon,” says Heuck.

Heuck is quick to point out that his team’s research has not only obvious applications in the world of pharmaceuticals and public health, but that it also advances our understanding of exactly how microbes infect healthy cells. “We wanted to study how pathogens worked,” he says, “and then suddenly we discovered that our findings can help solve a public-health problem.”

This research is published in the journal ACS Infectious Diseases.

More information: Hanling Guo et al, Cell-Based Assay to Determine Type 3 Secretion System Translocon Assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Using Split Luciferase, ACS Infectious Diseases (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00482

Source: Research team discovers how to sabotage antibiotic-resistant ‘superbugs’

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft