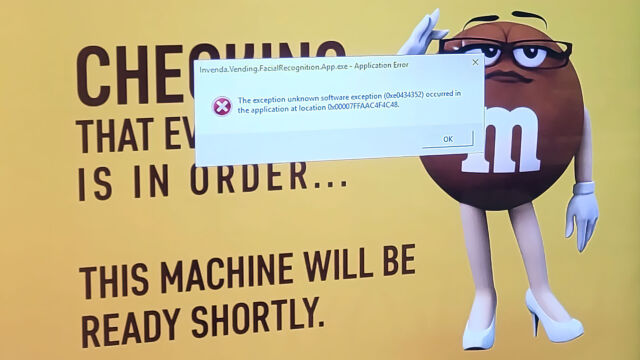

Pornhub has disabled its site in Texas to object to a state law that requires the company to verify the age of users to prevent minors from accessing the site.

Texas residents who visit the site are met with a message from the company that criticizes the state’s elected officials who are requiring them to track the age of users.

The company said the newly passed law impinges on “the rights of adults to access protected speech” and fails to pass strict scrutiny by “employing the least effective and yet also most restrictive means of accomplishing Texas’s stated purpose of allegedly protecting minors.”

Pornhub said safety and compliance are “at the forefront” of the company’s mission, but having users provide identification every time they want to access the site is “not an effective solution for protecting users online.” The adult content website argues the restrictions instead will put minors and users’ privacy at risk.

[…]

The announcement from Pornhub follows the news that Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) was suing Aylo, the pornography giant that owns Pornhub, for not following the newly enacted age verification law.

Paxton’s lawsuit is looking to have Aylo pay up to $1,600,000, from mid-September of last year to the date of the filing of the lawsuit and an additional $10,000 each day since filing.

[…]

Paxton released a statement on March 8, calling the ruling an “important victory.” The court ruled that the age verification requirement does not violate the First Amendment, Paxton said, saying he won in the fight against Pornhub and other pornography companies.

The state Legislature passed the age verification law last year, requiring companies that distribute sexual material that could be harmful to minors to confirm users to the platform are older than 18 years. The law asks users to provide government-issued identification or public or private data to verify they are of age to access the site.

Source: Pornhub disables website in Texas after AG sues for not verifying users’ ages | The Hill

Age verification is not only easily bypassed, but also extremely sensitive due to the nature of the documents you need to upload to the verification agency. Big centralised databases get hacked all the time and this one would be a massive target, also leaving people in it potentially open to blackmail, as they would be linked to a porn site – which for some reason Americans find problematic.