Companies that you likely have never heard of are hawking access to the location history on your mobile phone. An estimated $12 billion market, the location data industry has many players: collectors, aggregators, marketplaces, and location intelligence firms, all of which boast about the scale and precision of the data that they’ve amassed.

Location firm Near describes itself as “The World’s Largest Dataset of People’s Behavior in the Real-World,” with data representing “1.6B people across 44 countries.” Mobilewalla boasts “40+ Countries, 1.9B+ Devices, 50B Mobile Signals Daily, 5+ Years of Data.” X-Mode’s website claims its data covers “25%+ of the Adult U.S. population monthly.”

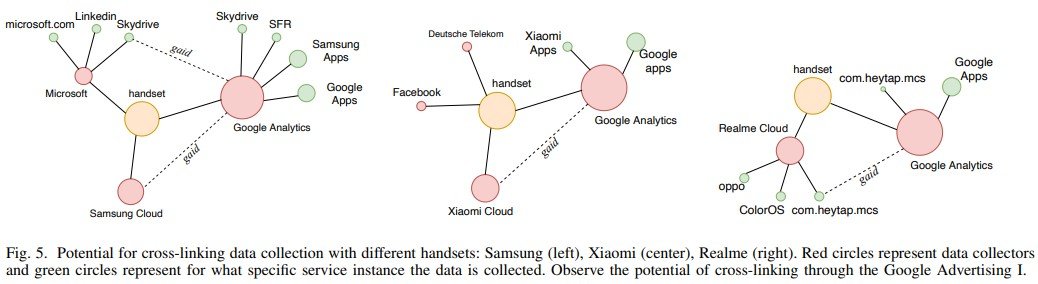

In an effort to shed light on this little-monitored industry, The Markup has identified 47 companies that harvest, sell, or trade in mobile phone location data. While hardly comprehensive, the list begins to paint a picture of the interconnected players that do everything from providing code to app developers to monetize user data to offering analytics from “1.9 billion devices” and access to datasets on hundreds of millions of people. Six companies claimed more than a billion devices in their data, and at least four claimed their data was the “most accurate” in the industry.

The Location Data Industry: Collectors, Buyers, Sellers, and Aggregators

The Markup identified 47 players in the location data industry

“40+ Countries, 1.9B+ Devices, 50B Mobile Signals Daily, 5+ Years of Data”

Narrative

Near

“There isn’t a lot of transparency and there is a really, really complex shadowy web of interactions between these companies that’s hard to untangle,” Justin Sherman, a cyber policy fellow at the Duke Tech Policy Lab, said. “They operate on the fact that the general public and people in Washington and other regulatory centers aren’t paying attention to what they’re doing.”

Occasionally, stories illuminate just how invasive this industry can be. In 2020, Motherboard reported that X-Mode, a company that collects location data through apps, was collecting data from Muslim prayer apps and selling it to military contractors. The Wall Street Journal also reported in 2020 that Venntel, a location data provider, was selling location data to federal agencies for immigration enforcement.

A Catholic news outlet also used location data from a data vendor to out a priest who had frequented gay bars, though it’s still unknown what company sold that information.

Many firms promise that privacy is at the center of their businesses and that they’re careful to never sell information that can be traced back to a person. But researchers studying anonymized location data have shown just how misleading that claim can be.

[…]

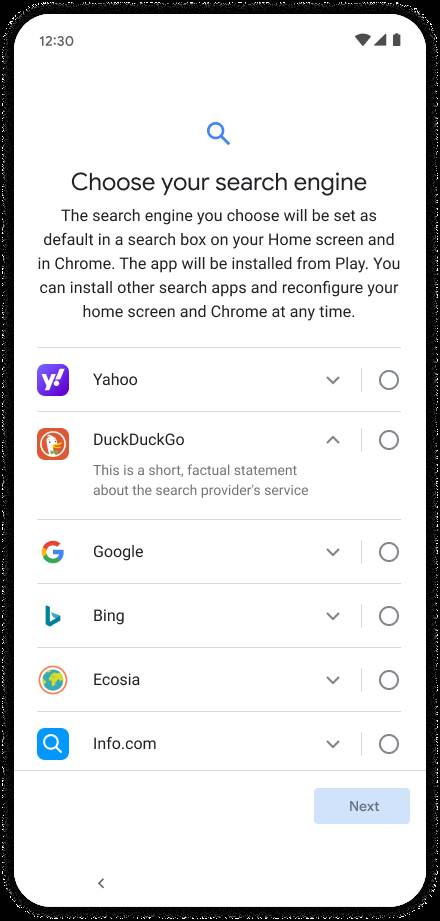

Most times, the location data pipeline starts off in your hands, when an app sends a notification asking for permission to access your location data.

Apps have all kinds of reasons for using your location. Map apps need to know where you are in order to give you directions to where you’re going. A weather, waves, or wind app checks your location to give you relevant meteorological information. A video streaming app checks where you are to ensure you’re in a country where it’s licensed to stream certain shows.

But unbeknownst to most users, some of those apps sell or share location data about their users with companies that analyze the data and sell their insights, like Advan Research. Other companies, like Adsquare, buy or obtain location data from apps for the purpose of aggregating it with other data sources

[…]

Companies like Adsquare and Cuebiq told The Markup that they don’t publicly disclose what apps they get location data from to keep a competitive advantage but maintained that their process of obtaining location data was transparent and with clear consent from app users.

[…]

Yiannis Tsiounis, the CEO of the location analytics firm Advan Research, said his company buys from location data aggregators, who collect the data from thousands of apps—but would not say which ones.

[…]

Into the Location Data Marketplace

Once a person’s location data has been collected from an app and it has entered the location data marketplace, it can be sold over and over again, from the data providers to an aggregator that resells data from multiple sources. It could end up in the hands of a “location intelligence” firm that uses the raw data to analyze foot traffic for retail shopping areas and the demographics associated with its visitors. Or with a hedge fund that wants insights on how many people are going to a certain store.

“There are the data aggregators that collect the data from multiple applications and sell in bulk. And then there are analytics companies which buy data either from aggregators or from applications and perform the analytics,” said Tsiounis of Advan Research. “And everybody sells to everybody else.”

Some data marketplaces are part of well-known companies, like Amazon’s AWS Data Exchange, or Oracle’s Data Marketplace, which sell all types of data, not just location data.

[…]

companies, like Narrative, say they are simply connecting data buyers and sellers by providing a platform. Narrative’s website, for instance, lists location data providers like SafeGraph and Complementics among its 17 providers with more than two billion mobile advertising IDs to buy from

[…]

To give a sense of how massive the industry is, Amass Insights has 320 location data providers listed on its directory, Jordan Hauer, the company’s CEO, said. While the company doesn’t directly collect or sell any of the data, hedge funds will pay it to guide them through the myriad of location data companies, he said.

[…]

Oh, the Places Your Data Will Go

There are a whole slew of potential buyers for location data: investors looking for intel on market trends or what their competitors are up to, political campaigns, stores keeping tabs on customers, and law enforcement agencies, among others.

Data from location intelligence firm Thasos Group has been used to measure the number of workers pulling extra shifts at Tesla plants. Political campaigns on both sides of the aisle have also used location data from people who were at rallies for targeted advertising.

Fast food restaurants and other businesses have been known to buy location data for advertising purposes down to a person’s steps. For example, in 2018, Burger King ran a promotion in which, if a customer’s phone was within 600 feet of a McDonalds, the Burger King app would let the user buy a Whopper for one cent.

The Wall Street Journal and Motherboard have also written extensively about how federal agencies including the Internal Revenue Service, Customs and Border Protection, and the U.S. military bought location data from companies tracking phones.

[…]

Outlogic (formerly known as X-Mode) offers a license for a location dataset titled “Cyber Security Location data” on Datarade for $240,000 per year. The listing says “Outlogic’s accurate and granular location data is collected directly from a mobile device’s GPS.”

At the moment, there are few if any rules limiting who can buy your data.

Sherman, of the Duke Tech Policy Lab, published a report in August finding that data brokers were advertising location information on people based on their political beliefs, as well as data on U.S. government employees and military personnel.

“There is virtually nothing in U.S. law preventing an American company from selling data on two million service members, let’s say, to some Russian company that’s just a front for the Russian government,” Sherman said.

Existing privacy laws in the U.S., like California’s Consumer Privacy Act, do not limit who can purchase data, though California residents can request that their data not be “sold”—which can be a tricky definition. Instead, the law focuses on allowing people to opt out of sharing their location in the first place.

[…]

“We know in practice that consumers don’t take action,” he said. “It’s incredibly taxing to opt out of hundreds of data brokers you’ve never even heard of.”

[…]

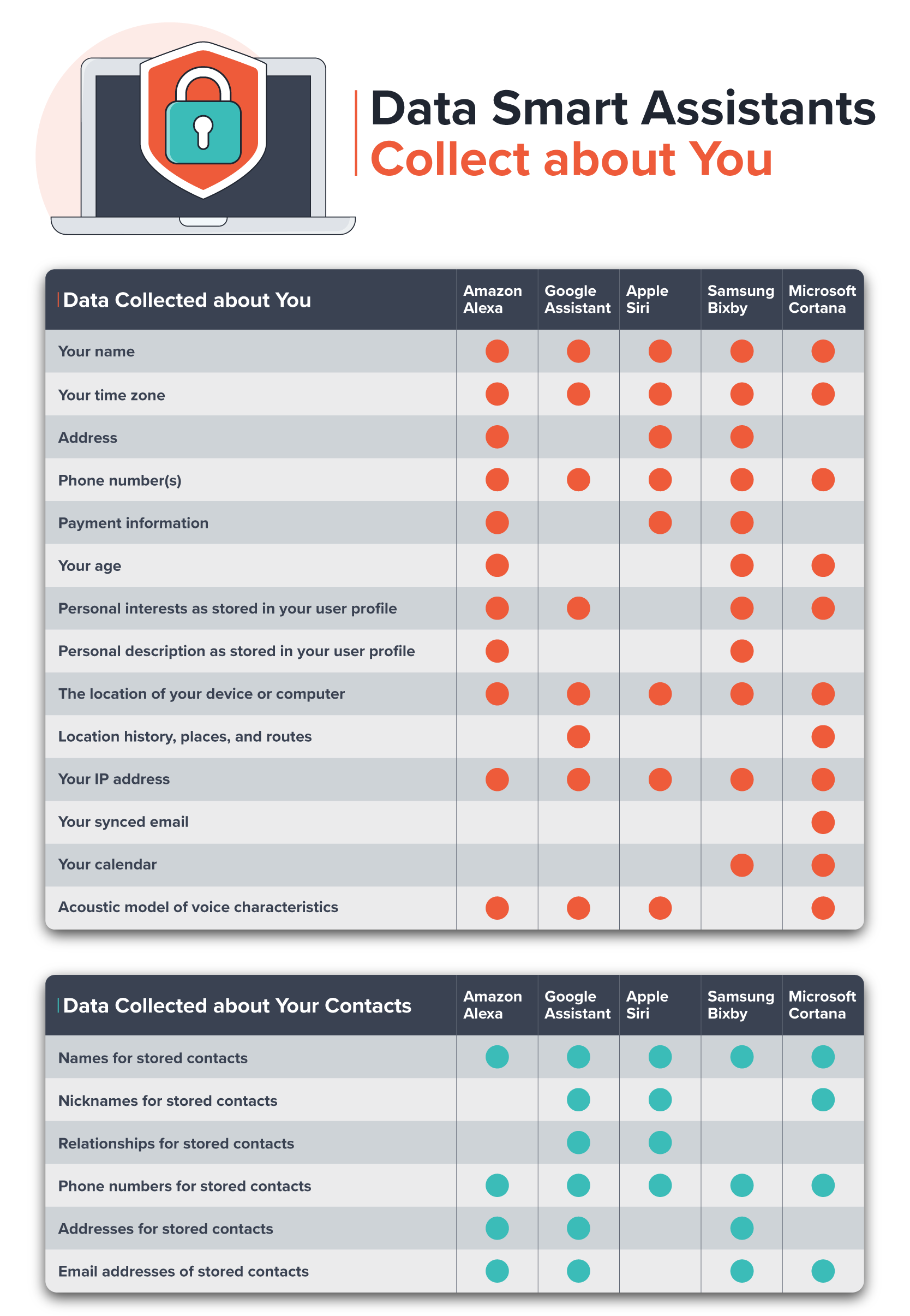

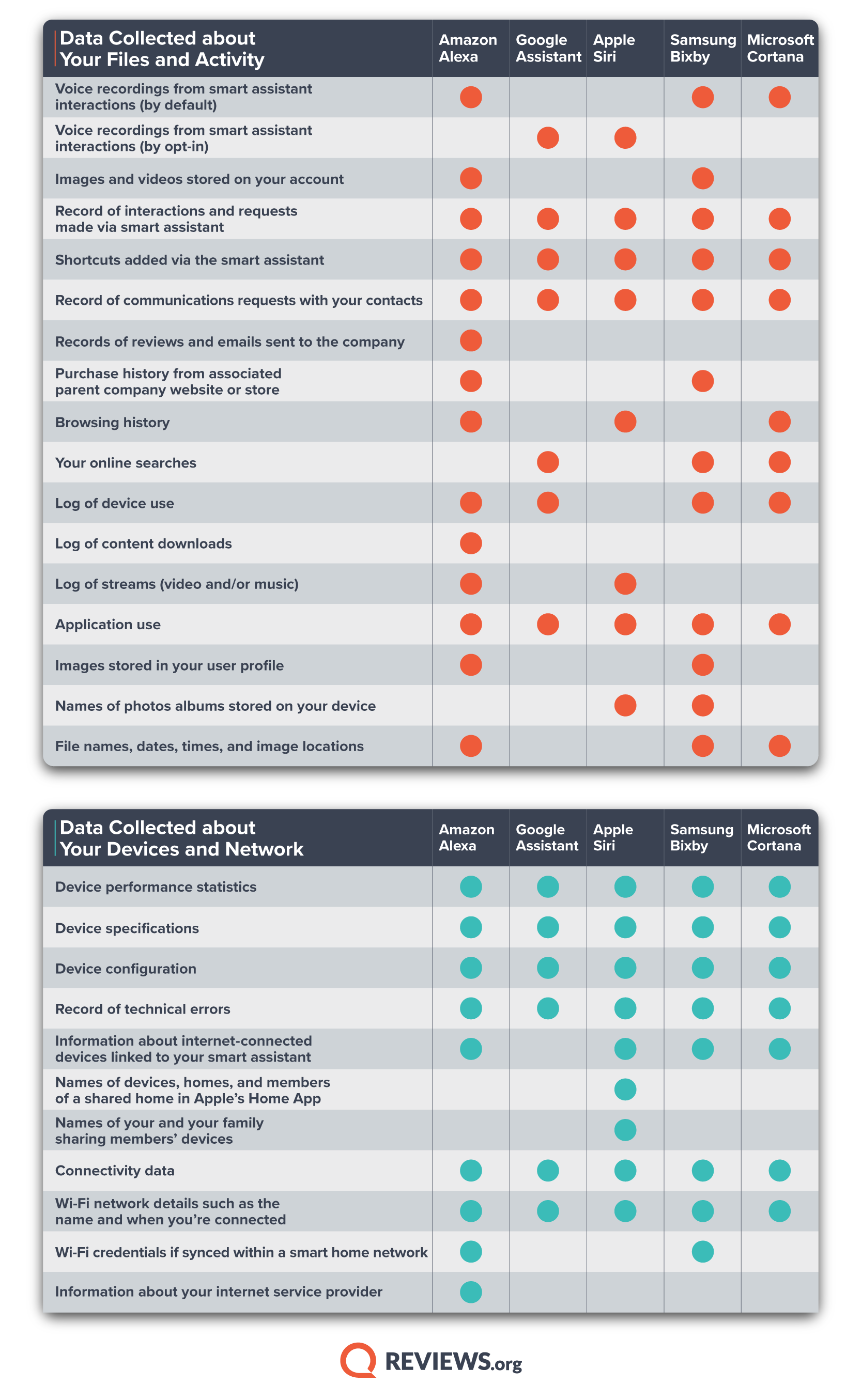

Our smart devices are listening. Whether it’s personally identifiable information, location data, voice recordings, or shopping habits, our smart assistants know far more than we realize.