Cellebrite makes software to automate physically extracting and indexing data from mobile devices. They exist within the grey – where enterprise branding joins together with the larcenous to be called “digital intelligence.” Their customer list has included authoritarian regimes in Belarus, Russia, Venezuela, and China; death squads in Bangladesh; military juntas in Myanmar; and those seeking to abuse and oppress in Turkey, UAE, and elsewhere. A few months ago, they announced that they added Signal support to their software.

[…]

They produce two primary pieces of software (both for Windows): UFED and Physical Analyzer.

UFED creates a backup of your device onto the Windows machine running UFED (it is essentially a frontend to

adb backupon Android and iTunes backup on iPhone, with some additional parsing). Once a backup has been created, Physical Analyzer then parses the files from the backup in order to display the data in browsable form.When Cellebrite announced that they added Signal support to their software, all it really meant was that they had added support to Physical Analyzer for the file formats used by Signal. This enables Physical Analyzer to display the Signal data that was extracted from an unlocked device in the Cellebrite user’s physical possession.

One way to think about Cellebrite’s products is that if someone is physically holding your unlocked device in their hands, they could open whatever apps they would like and take screenshots of everything in them to save and go over later. Cellebrite essentially automates that process for someone holding your device in their hands.

[…]

we were surprised to find that very little care seems to have been given to Cellebrite’s own software security. Industry-standard exploit mitigation defenses are missing, and many opportunities for exploitation are present.

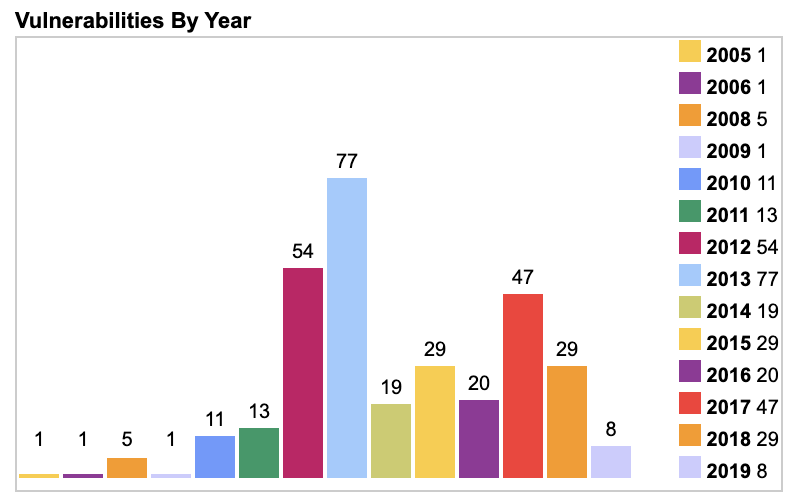

As just one example (unrelated to what follows), their software bundles FFmpeg DLLs that were built in 2012 and have not been updated since then. There have been over a hundred security updates in that time, none of which have been applied.

The exploits

Given the number of opportunities present, we found that it’s possible to execute arbitrary code on a Cellebrite machine simply by including a specially formatted but otherwise innocuous file in any app on a device that is subsequently plugged into Cellebrite and scanned. There are virtually no limits on the code that can be executed.

For example, by including a specially formatted but otherwise innocuous file in an app on a device that is then scanned by Cellebrite, it’s possible to execute code that modifies not just the Cellebrite report being created in that scan, but also all previous and future generated Cellebrite reports from all previously scanned devices and all future scanned devices in any arbitrary way (inserting or removing text, email, photos, contacts, files, or any other data), with no detectable timestamp changes or checksum failures. This could even be done at random, and would seriously call the data integrity of Cellebrite’s reports into question.

Any app could contain such a file, and until Cellebrite is able to accurately repair all vulnerabilities in its software with extremely high confidence, the only remedy a Cellebrite user has is to not scan devices.

[…]

In completely unrelated news, upcoming versions of Signal will be periodically fetching files to place in app storage. These files are never used for anything inside Signal and never interact with Signal software or data, but they look nice,

[…]

We have a few different versions of files that we think are aesthetically pleasing, and will iterate through those slowly over time.

Nice – so installing Signal on your phone means there is a real possibility that you will get a Cellebrite breaking file on your phone. If they tap you, they will unknowingly break the Cellebrite unit permanently.