Penetration testers looking at commercial shipping and oil rigs discovered a litany of security blunders and vulnerabilities – including one set that would have let them take full control of a rig at sea.

Pen Test Partners (PTP), an infosec consulting outfit that specialises in doing what its name says, reckoned that on the whole, not many maritime companies understand the importance of good infosec practices at sea. The most eye-catching finding from PTP’s year of maritime pentesting was that its researchers could have gained a “full compromise” of a deep sea drilling rig, as used for oil exploration.

PTP’s Ken Munro explained, when The Register asked the obvious question, that this meant “stop engine, fire up thrusters (dynamic positioning system), change rudder position, mess around with navigation, brick systems, switch them off, you name it.”

The firm’s Nigel Hearne explained that many maritime tech vendors have a “variable” approach to security.

Making heavy use of the word “poor” to summarise what he had seen over the past year, Hearne wrote that he and his colleagues had examined everything from a deep water exploration and the aforementioned drilling rig to a brand new cruise ship to a Panamax container vessel, and a few others in between.

Munro also published a related blog post this week.

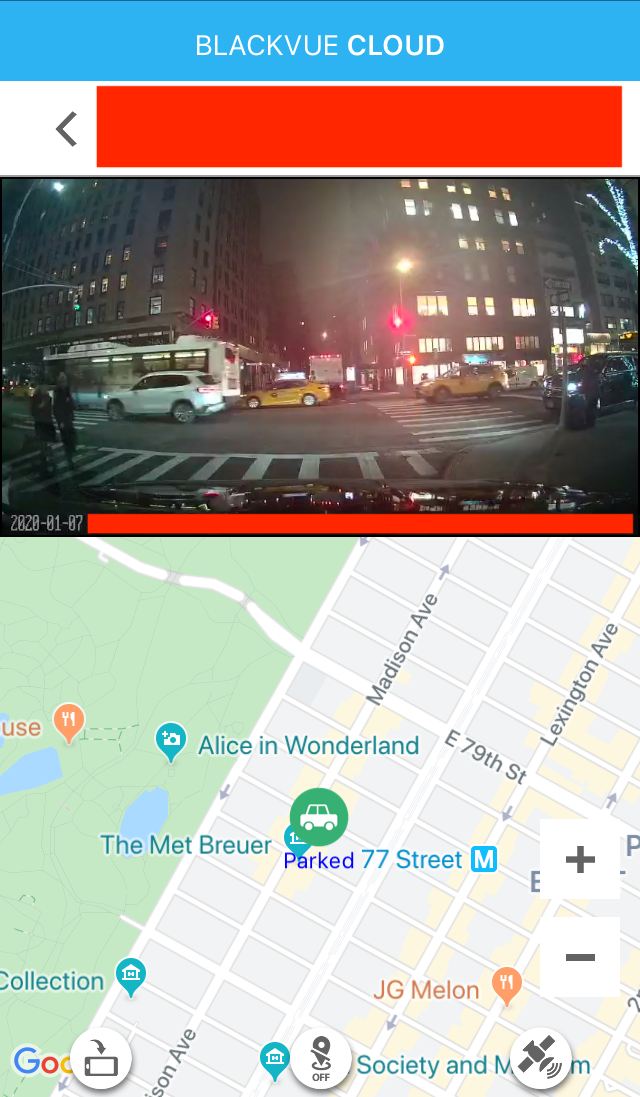

Among other things the team found were clandestine Wi-Fi access points in non-Wi-Fi areas of ships (“they want to stream tunes/video in a work area that they can’t get crew Wi-Fi in,” said Munro), and crews bridging designed gaps between ships’ engineering control systems and human interface systems.

Why were seafarers doing something that seems so obviously silly to an infosec-minded person? Munro told us: “Someone needs to administrate or monitor systems from somewhere else in the vessel, saving a long walk. Ships are big!”

Another potential explanation proferred by Munro could apply to cruise ship crews where Wi-Fi is generally a paid-for, metered commodity: “Their personal satellite data allowance has been used up, so they put a rogue Wi-Fi AP on to the ship’s business network where there are no limits.”

A Panamax vessel (the largest size of ship that can pass through the Panama Canal, the vital central American shipping artery between the Atlantic and Pacific) can be up to 294 metres (PDF, page 8 gives the measurements) from stem to stern. A crew member needing to move from, say, bow thruster to main machinery control room in the aft part of the ship and back again will spend significant amounts of time doing so. It’s far easier to jury-rig remote access than do all that walking.

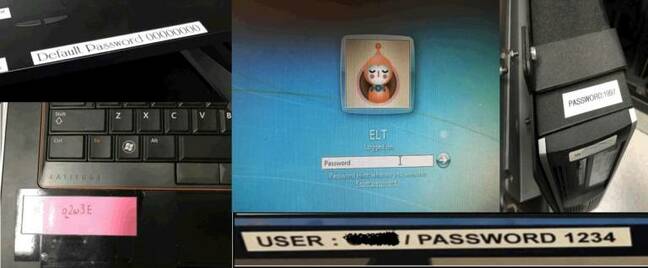

PTP also found that old infosec chestnut, default and easy-to-guess passwords – along with a smattering of stickers on PCs with passwords in plaintext.

Default passwords aboard ships. Pic: Pen Test Partners

“One of the biggest surprises (not that I should have been at all surprised in hindsight) is the number of installations we still find running default credentials – think admin/admin or blank/blank – even on public facing systems,” sighed Hearne, detailing all the systems he found that were using default creds – including an onboard CCTV system.

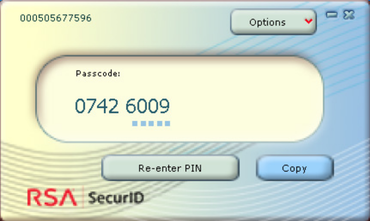

The pentesters also found “hard coded credentials” embedded in critical items including a ship’s satcom (satellite comms mast) unit, potentially allowing anyone aboard the ship to log in and piggyback off the owners’ paid-for internet connection – or to cut it off