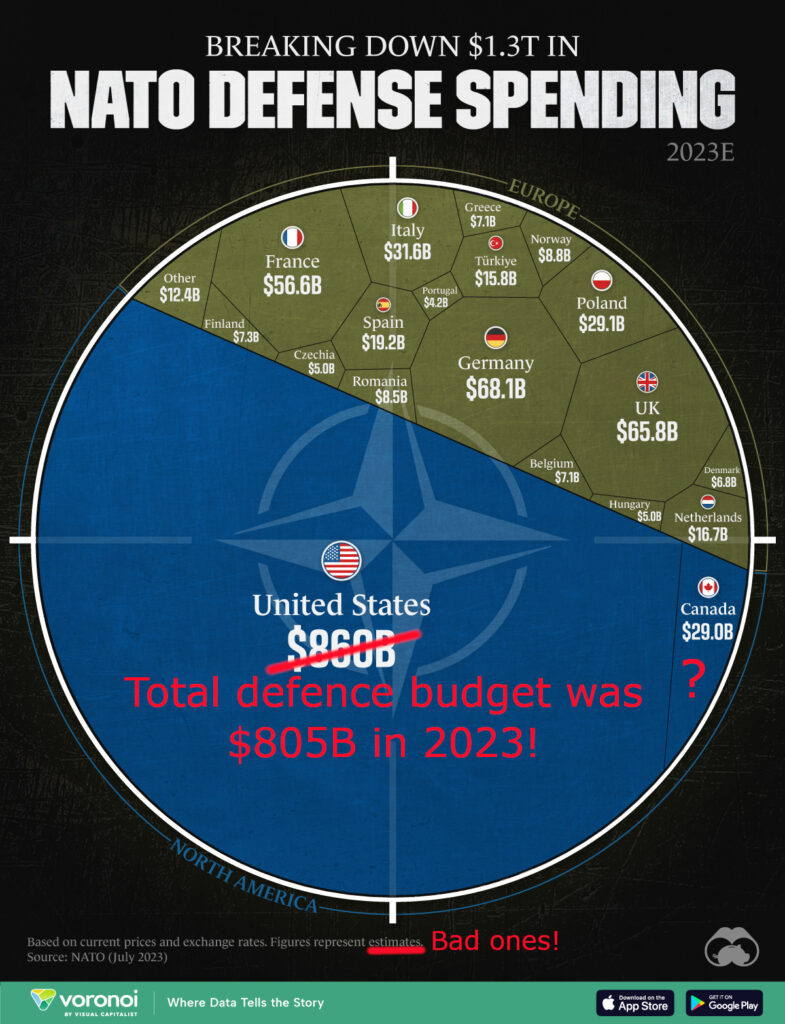

The visualisation of US vs EU spending on NATO going the rounds is pretty suspect: The Blue area contains not just the USA, but also Canada. The US defence budget is incorrect. It fails to take into account that the US is a global player with ambitions and commitments beyond NATO. It doesn’t show that EU defence spending is larger than that of Russia and China. There is no mention of the pressure the USA exerts on it’s NATO allies to Buy American – and the staggering amount the US shop window filled with pretty poor products (such as the F-35) is valued at. There is no mention of the years of fragmentation inflicted on the EU by the US to insure that the EU was never able to create economies of scale, or even a common security and defence policy. Finally, the scale of US defence spending comes at a cost. Social and welfare spending is much much lower in the US than in the EU, which helps explain the low levels of education, happiness, social mobility, etc in the US. A sacrifice the EU does not seem to want to make.

Comparing Apples and Pears

Original Source: Breaking Down $1.3T in NATO Defense Spending

US Budget source: The Federal Budget in Fiscal Year 2023: An Infographic | Congressional Budget Office

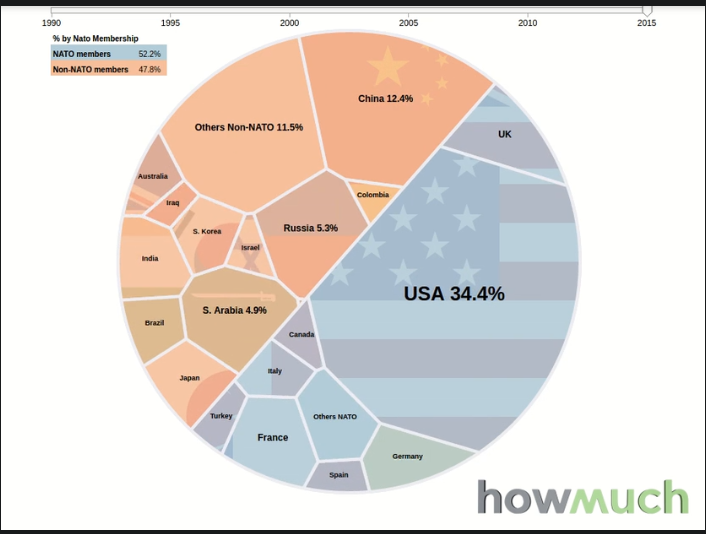

[…] the moral high ground on which the United States stands to shame allies on defense spending is partly an illusion. There is no question Washington spends significant resources on defense, but likening total US defense expenditures to those of its allies is not an appropriate comparison. Unlike most other NATO nations, the United States is a global actor with commitments extending to the Middle East and IndoPacific as well as Europe. Most European defense capabilities are expended in theater or in direct support of NATO missions like in Afghanistan, whereas only a portion of the US defense budget is dedicated to transatlantic security.[…] the common pretense in US policy circles that the entirety of US defense spending is counted toward European security is logically unsound.

[…] In addition, continental US territory falls under NATO’s collective-defence commitment, so US forces devoted to US continental defence also in effect amount to a NATO commitment to defend the Alliance’s largest member. The same goes particularly for Canada’s commitment to North American defence. But that commitment is Alliance-wide, and – as has been often remarked – the one activation of NATO’s Article 5 collective-defence undertaking was in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the US, when the rest of the Alliance quickly supplemented US air defences with Alliance-operated AWACS airborne early-warning aircraft.

However, America is spending its defence dollars principally for its own security needs, as well as to support a range of interests and allies in other regions around the world, not exclusively Europe. As one can see, the balance sheet is complicated to say the least – those assets and resources are developed first and foremost for national interests and therefore have a dual US/external-security use. […]

Source: The US and its NATO allies: costs and value | IISS

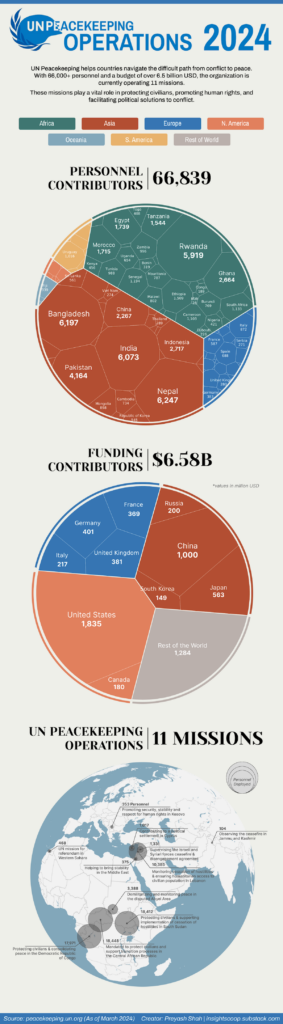

This focus on US security needs is particularly visible when you look at the amount of troops the US commits to United Nations peacekeeping operations.

The U.S. [….] currently has only 27 personnel in the peacekeepers, as of November 2023. Of them, 21 are staff officers, four are “experts on mission,” and two are police; none are troops.

Other countries that have zero “boots on the ground” include: Canada, Japan, and Australia.

Source: Charted: Contributions to UN Peacekeeping Forces by Country

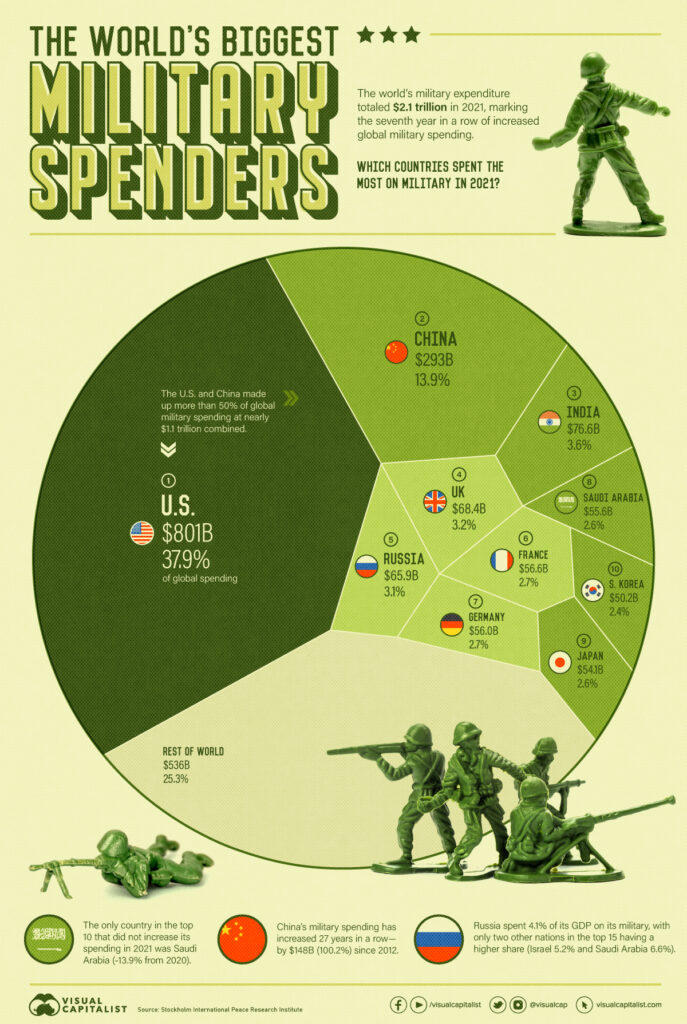

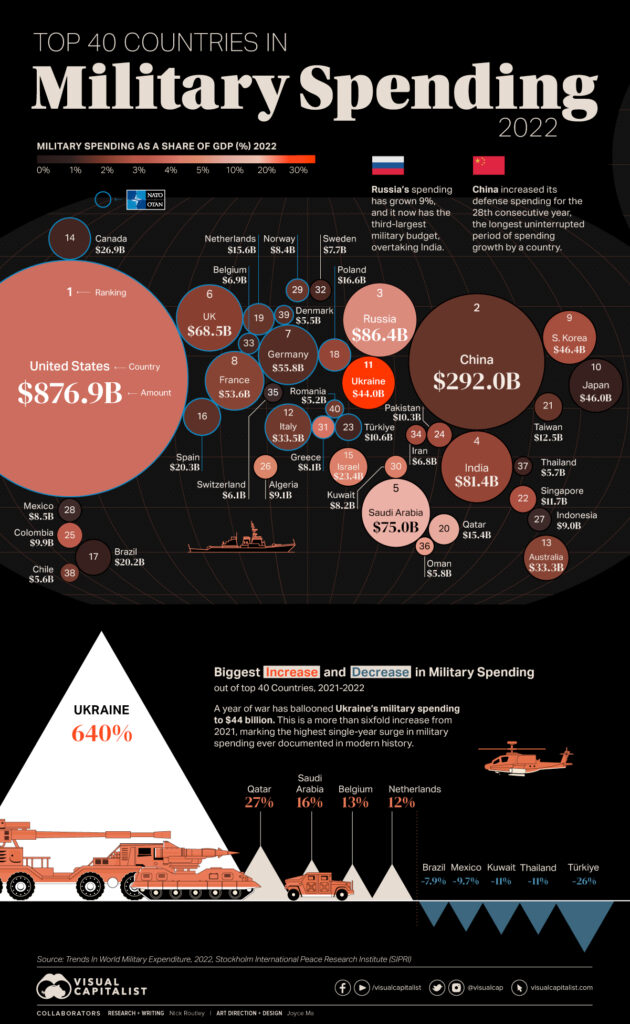

US Spending is about equal to Asian spending, and only slightly higher than the largest EU contributors

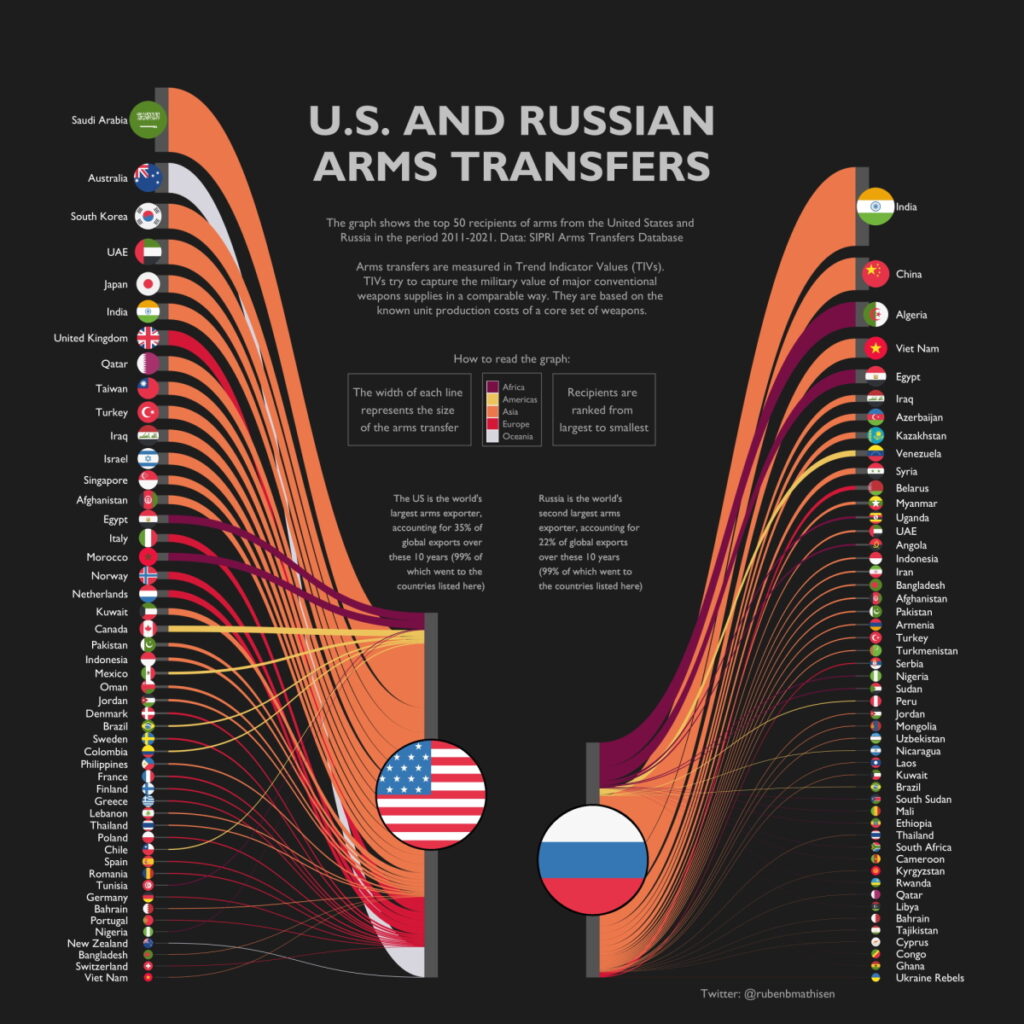

This lack of actual boots on the ground but amount of expenditure points to what the United States is really supporting: it’s defence industry.

US Business interests winning – Coercion by the US to buy US products

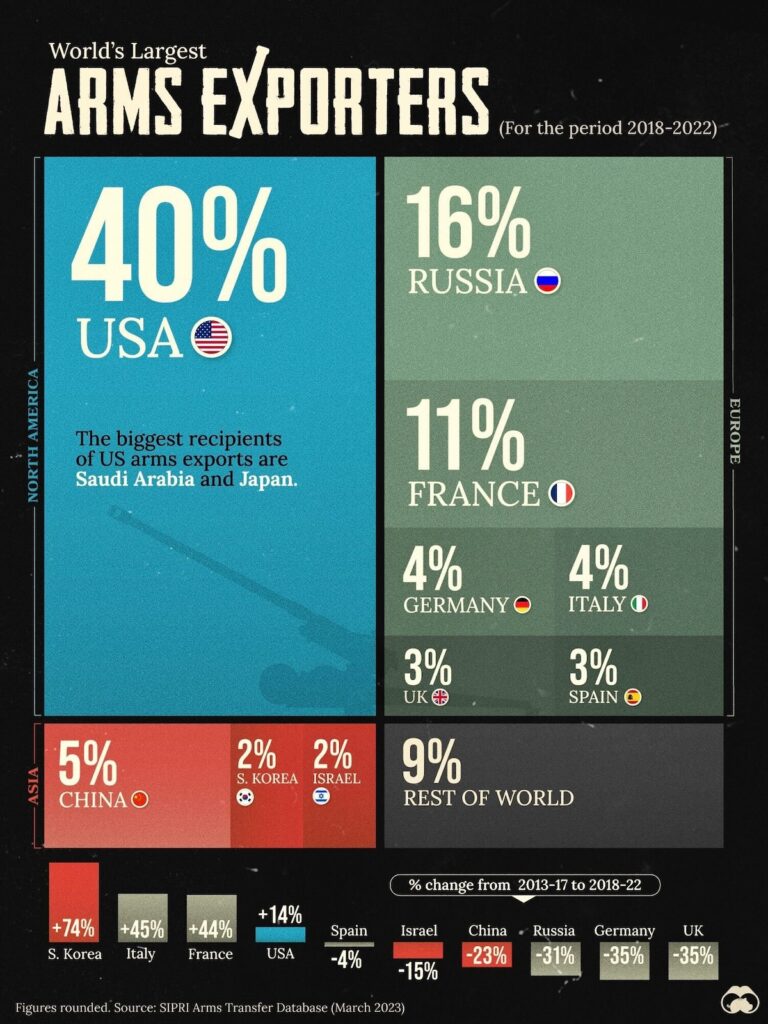

The US uses strong arm tactics to sell their products to countries that have an indigenous arms industry – usually composed of better and cheaper to operate products. The US, however, won’t take no for an answer – and US companies profit massively. How massively? See below.

[…] NATO creates a market for defence sales. Over the last two years, NATO Allies have agreed to purchase 120 billion dollars’ worth of weapons from U.S. defence companies. Including thousands of missiles to the U.K, Finland and Lithuania, Hundreds of Abrams tanks to Poland and Romania, And hundreds of F-35 aircraft across many European Allied nations – a total of 600 by 2030. From Arizona to Virginia, Florida to Washington state, American jobs depend on American sales to defence markets in Europe and Canada. What you produce keeps people safe. What Allies buy keeps American businesses strong. So NATO is a good deal for the United States. […]

The U.S. alone represents a quarter of the world economy. But together, with NATO Allies, we represent half of the world’s economic might. And half of the world’s military might. Together, we have world-class militaries, vast intelligence networks, more defence spending, and unique diplomatic leverage.[…]

A total of 23 per cent of US arms exports went to states in Europe in 2018–22, up from 11 per cent in 2013–17. Three of the USA’s North Atlantic 4 sipri fact sheet Treaty Organization (NATO) partners in the region were among the 10 largest importers of US arms in 2018–22: the UK accounted for 4.6 per cent of US arms exports, the Netherlands for 4.4 per cent and Norway for 4.2 per cent.

[…]

Arms imports by European states were 47 per higher in 2018–22 than in 2013–17. The biggest European arms importer in 2018–22 was the UK, which was the 13th largest arms importer in the world, followed by Ukraine (see box 2) and Norway, ranking 14th and 15th respectively. The USA accounted for 56 per of the region’s arms imports in 2018–22, Russia for 5.8 per (mainly to Belarus) and Germany for 5.1 per cent.

European NATO states

Largely in response to the deteriorating security environment in the region, NATO states in Europe increased their arms imports by 65 per cent between 2013–17 and 2018–22. The USA accounted for 65 per cent of total arms imports by European NATO states and the NATO organization itself (see table 2) in 2018–22. The next biggest suppliers were France (8.6 per cent) and South Korea (4.9 per cent). The arms imports of European NATO states are expected to continue to rise in the coming years, based on existing programmes for arms imports. These include orders placed before the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and several large orders announced afterwards. Some of the orders placed in 2022 were the result of accelerated procurement processes implemented in response to the war in Ukraine. For example, in the first four years of the period (2018–21), Poland’s most notable arms import orders included 32 combat aircraft and 4 missile and air defence systems from the USA; however, in 2022 Poland announced new orders for 394 tanks, 96 combat helicopters and 12 missile and air defence systems from the USA; 48 combat aircraft, 1000 tanks, 672 self-propelled guns and 288 multiple rocket launchers from South Korea; and 3 frigates from the UK. After an accelerated procurement process, Germany ordered 35 combat aircraft from the USA in late 2022. These are specifically for carrying nuclear weapons owned by the USA and will replace existing aircraft that have this task.

Source: Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2022 | SIPRI

And if you don’t buy US equipment, or don’t want to? You are leant on before you buy and after you buy. The following show rare but explicitly how the US conducts ‘business’

The U.S. government expressed disappointment with the Czech Republic and Hungary for their December moves toward acquiring non-American-made fighter jets. The rare public criticism of U.S. NATO allies comes as Poland also considers purchasing new fighter jets for its air force.

Speaking December 18, State Department spokesman Richard Boucher said that the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland—all of which joined NATO in 1999—should not jeopardize more urgent military needs and reforms necessary for the three countries to work more effectively with NATO’s other 16 members by purchasing advanced fighter jets, which can cost up to tens of millions of dollars apiece.

But Boucher continued by saying, “If you’re going to buy [combat aircraft], buy American.” Adding that “we think we make the best,” he said that Secretary of State Colin Powell “has raised the interest of American companies in selling airplanes” during meetings with officials from the three countries. […]

The Pentagon estimated in June that a sale of 60 U.S. F-16 fighters to Poland would cost $4.3 billion. This price tag includes missiles and bombs to arm the aircraft as well as U.S. training.

Source: U.S. Urges 3 NATO Countries to Buy U.S. Fighters | Arms Control Association

MR. BOUCHER: The Secretary has been a staunch supporter of American aircraft sales, and in his meetings from the very beginning of the Administration, he has raised the fortunes of American companies and the fact that we make the best airplanes in the world. He has pressed that in a variety of meetings. So we are disappointed that the Czech Republic and Hungary recently took steps forward in procuring advanced supersonic fighter aircraft […] The Secretary has raised these issues about the cost, the spending, the implication for other programs. But in the end, he has always said if you’re going to buy airplanes, you ought to buy American ones

QUESTION: So do you think that their purchase of these jets and using them could affect badly — adversely affect NATO in some way?

MR. BOUCHER: We have — I think we have tried to make clear all along that, as nations address these force requirements and these purchases, they needed to consider the overall impact on military reform programs and abilities to meet their broader global force obligations to NATO. And those are important questions that we think need to be considered.

[…]

MR. BOUCHER: Yes. If you’re going to buy, buy American. But consider carefully how you can meet your overall obligations.

QUESTION: Richard, you seem to be saying — let me get this straight. Do you think it was unwise of these two governments to decide to buy planes instead of doing something else with the money?

MR. BOUCHER: I don’t think I would use your language. I think I will stick to my language, thanks.

QUESTION: What was your language — you think it was what, then? You think —

MR. BOUCHER: As I said, we think that they should avoid major defense procurements, which could jeopardize other urgently needed military reforms.

QUESTION: But if they are going to make them, they should buy from the States and not from —

MR. BOUCHER: Yes

[…]

QUESTION: I don’t understand the interoperability thing that you just brought up with Barry. Because, I mean, are you saying that, say, French aircraft or British aircraft are not interoperable within the NATO scheme of things? I mean, these countries fly their own planes. Why can’t — why do the Czechs have to buy your planes, and why can’t they buy from someone — I mean, I can understand if they were buying from China, or from — (laughter) — what’s the deal?

[…]

MR. BOUCHER: Nobody said they can’t buy some other airplane. We haven’t argued that these other airplanes cannot be interoperable with NATO — with American airplanes or NATO airplanes or other airplanes that NATO maintains in its inventory. Our view has been that when it comes to airplanes, first of all, we make the best ones. And second of all, we make airplanes that have been deployed throughout the world, that have been proven in combat, that have been proven in lots of different situations. And they have a demonstrated record of interoperability, as well as performance. And we think we make the best. So we make that clear to other countries when we talk to them.

QUESTION: But can’t you let, you know, Boeing and Lockheed Martin make their own sales pitch for them?

MR. BOUCHER: We like to support American workers, American companies.

QUESTION: All right.

QUESTION: Sort of related to that. Can you just expand on how the Secretary has raised the fortunes of American aircraft companies? I’m just — that was what you said originally —

MR. BOUCHER: Perhaps it’s not the best phrase. He has raised the interests of American aircraft companies in selling airplanes.

QUESTION: But he didn’t — I just want to —

MR. BOUCHER: I didn’t say he — that he — I didn’t mean to say that he brought more money their way. No.

QUESTION: Okay. I just —

MR. BOUCHER: That was a bad — perhaps a bad choice of words. But that was not the implication. He has raised the interest of American companies in selling airplanes.

US Interference with common EU Defence policy

The following excerpts show the US way of thinking re common EU defence policy. The US has spent decades strong arming the EU into not working together. They used scare tactics and nonsense texts in order to assure US supremacy within NATO as well as globally. Of course, there is a lot to be said that the EU allowed themselves to be bossed around, and the weak spines of the EU politicians (and of course their wallets, as they were still paying back the Marshall Plan to uncertain terms) can be shown. At the same time, their military advisors were playing in terms of self interest – they wanted to keep playing with US toys and at US facilities and at the scale the US exercises were held and didn’t see that if they had a single EU defence policy, they would be able to play at that scale – but with toys and capabilities they got to design themselves, instead of riding on US coat tails.

From a military standpoint, the European Union’s Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) defies logic. Why would the European allies seek to create a competing military force outside NATO when worried about American isolationism and when unable and unwilling to dedicate the necessary resources? This article suggests an alternative motive behind the European Union’s establishment of a defense program—the development and enhancement of a “European identity.” In short, the ESDP is designed in no small part to further the project of nation-building in a broadening European Union. This article proposes a social-constructivist framework for analyzing this development.

Source: European Security and Defense Policy Demystified | Armed Forces and Society

The level of Europe’s defense spending and the size of its collective forces in uniform should make it a global power with one of the strongest militaries in the world. But Europe does not act as one on defense, even though it formed a political union almost 30 years ago. Europe’s military strength today is far weaker than the sum of its parts. This is not just a European failure; it is also fundamentally a failure of America’s post-Cold War strategy toward Europe—a strategy that remains virtually unchanged since the 1990s.

Europe’s dependence on the United States for its security means that the United States possesses a de facto veto on the direction of European defense. Since the 1990s, the United States has typically used its effective veto power to block the defense ambitions of the European Union. This has frequently resulted in an absurd situation where Washington loudly insists that Europe do more on defense but then strongly objects when Europe’s political union—the European Union—tries to answer the call. This policy approach has been a grand strategic error—one that has weakened NATO militarily, strained the trans-Atlantic alliance, and contributed to the relative decline in Europe’s global clout. As a result, one of America’s closest partners and allies of first resort is not nearly as powerful as it could be.

[…]

U.S. policy has consistently opposed EU defense efforts since the late 1990s, arguing that EU defense efforts would undermine NATO. State Department officials’ oft-repeated claim, virtually unchanged over the past three decades, is that an EU defense structure would “duplicate” NATO, making the treaty organization obsolete. Democratic and Republican administrations have repeated the mantra “no duplication” so often that it has become U.S. policy doctrine.5 But rarely, if ever, is the concern about possible duplication actually unpacked and assessed.

[…]

The limited nature of current EU defense efforts is no doubt the fault of the EU. But the immense agency the United States has on European defense questions is also undeniable. Since the 1990s, the United States has wielded its influence, often by mobilizing EU members that are most dependent on U.S. security guarantees to block or constrain EU efforts.

Thus, for nearly 25 years, the United States has opposed the federalization of European foreign and defense policy at the EU level.

[…]

in December 1998, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright struck a different tone than her predecessor 45 years earlier.13 In just a few short sentences, she laid out Washington’s concerns. She explained that the effort to create a European Security and Defense Identity (ESDI) must avoid “de-linking ESDI from NATO, avoid duplicating existing efforts, and avoid discriminating against non-EU members.” Secretary Albright’s address became known as the “three Ds”—no duplicating, discriminating, or delinking.

Secretary Albright’s speech was prompted by what seemed, at the time, like a stunning European breakthrough on defense. Just four days prior, a remarkable agreement was signed by U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair and French President Jacques Chirac in St. Malo, France. There, the two largest European military powers agreed to support the formation of a 60,000 strong European force.

[…]

Secretary Albright’s “three Ds,” if rigidly interpreted, left little room for the EU to expand into defense. The speech became a de facto doctrine that has been rigidly adhered to ever since, even if that was not the original intent. The subsequent two decades have shown that any EU effort could be accused of being duplicative or discriminating against non-EU states.

[…]

U.S. Secretary of Defense William Cohen warned in his final NATO summit in 2000—in what The Washington Post described as an “unusually passionate speech” at a NATO Defense Ministerial—that “there will be no EU caucus in NATO” and that NATO could become “a relic of the past” should the EU move forward with its proposal to set up a rapid reaction force.16

[…]

Indeed, when the Bush administration took office in 2001, it pushed NATO to create an alternative to the EU’s rapid reaction force proposal, the NATO Response Force.

[…]

In a letter that caught Brussels completely off guard, the State Department’s Under Secretary of State Andrea Thompson and Under Secretary of Defense Ellen Lord warned the EU of retribution if it did not include the United States or third parties to participate in PESCO projects.33 Returning to the concerns that Secretary Albright had voiced 20 years prior, they argued that there was a risk of “EU capabilities developing in a manner that produces duplication, non-interoperable military systems, diversion of scarce defense resources, and unnecessary competition between NATO and the EU.”34 Yet the inclusion that the Trump administration demanded is not reciprocal, as the United States would not allow European defense companies similar access to the U.S. defense procurements.35 The U.S. Congress wants American taxpayer dollars to go to American companies, and yet the United States expects the EU to operate differently.

The Trump administration maintained U.S. opposition to EU defense, less to preserve NATO equities and more for petty, parochial purposes: the interests of U.S. defense companies. As Nick Witney of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) points out, the United States “aggressively lobbied against Europeans’ efforts to develop their defence industrial and technological base.”36 This exposes the contradictory nature of U.S. policy: The United States expects Europe to get its act together on defense but to not spend its taxpayer euros on European companies. Indeed, it is hard to see Europeans spending robustly on defense if that spending does not support European jobs and innovation.

[…]

The problem with the current state of European defense is not fundamentally about spending. Collectively, European defense spending levels should actually be enough to put forth a fighting force roughly on par with other global powers. While it is difficult to compare in absolute numbers given the differences in purchasing power, when taken together, the EU spends more on defense than either Russia or China, at nearly $200 billion per year.38

[…]

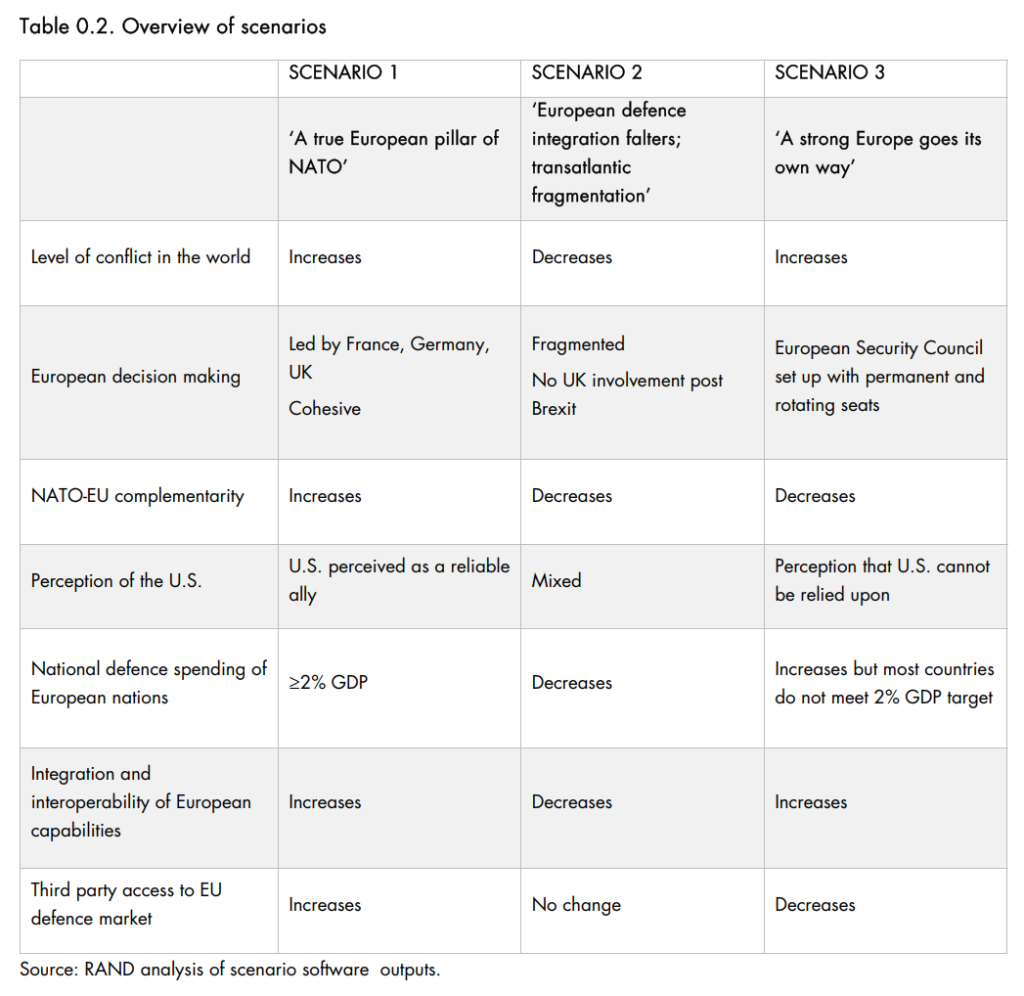

RAND is enormously respected and see the fear instigated in each of their possible scenarios for a common EU defence policy – they apparently lead to greater conflict in the world and otherwise NATO suffers.

This study explored three possible futures of European strategic autonomy in defence to understand their policy implications

[….] Experts varied in their views of which scenario was most plausible, with European interviewees tending to lean towards Scenario 1, which envisages development of a strong European pillar of NATO, on the basis of current trends; and US interviewees expressing some scepticism of this being plausible in the short term (next five years or so). As a result, several US interviewees noted that elements of Scenario 2, which envisage a faltering EU defence integration and transatlantic fragmentation, might be more plausible. A strong Europe that does not rely on NATO for access to military capabilities and structures, as envisaged in Scenario 3, was generally perceived as implausible in the short (five year) term considered by this study

A militarily stronger EU has clear benefits for NATO and the U.S., but the path towards it is not without risks – particularly if it diverges from NATO

A strong European pillar within NATO was largely seen by experts as advantageous for all actors considered: bringing greater military strength to NATO, while creating a militarily stronger partner to the U.S. in a time of intense global competition. Conversely, a capable EU that duplicates or disregards NATO was seen as a threat to transatlantic relations. A number of US interviewees also perceived a risk that the U.S. would lose influence in Europe and would risk divergence of foreign and security policy. This was seen as particularly concerning vis-à-vis other countries the U.S. perceives as competitors and adversaries (e.g. China, Russia) but which some in the EU may not perceive in the same way. The risks accompanying such divergence due to a militarily independent EU were seen as not too dissimilar to those of the opposite extreme of a fragmented Europe.vi A militarily fragmented EU, then, could weaken NATO in terms of defence capabilities but could also mean a further relative increase in US influence within NATO, potentially driving greater coherence of the Alliance. Overall, however, NATO’s credibility – tightly knit with the strength, effectiveness and coordination of military capabilities of the 30 allies – would likely suffer in this scenario. This is because most EU member states are also NATO members and the forces and capabilities they have are the same – whether used for EU CSDP missions or operations through NATO. US foreign and security policy ambitions could also suffer if one of its crucial allies were to become fragmented and militarily weak

[…]

Other Spending Priorities

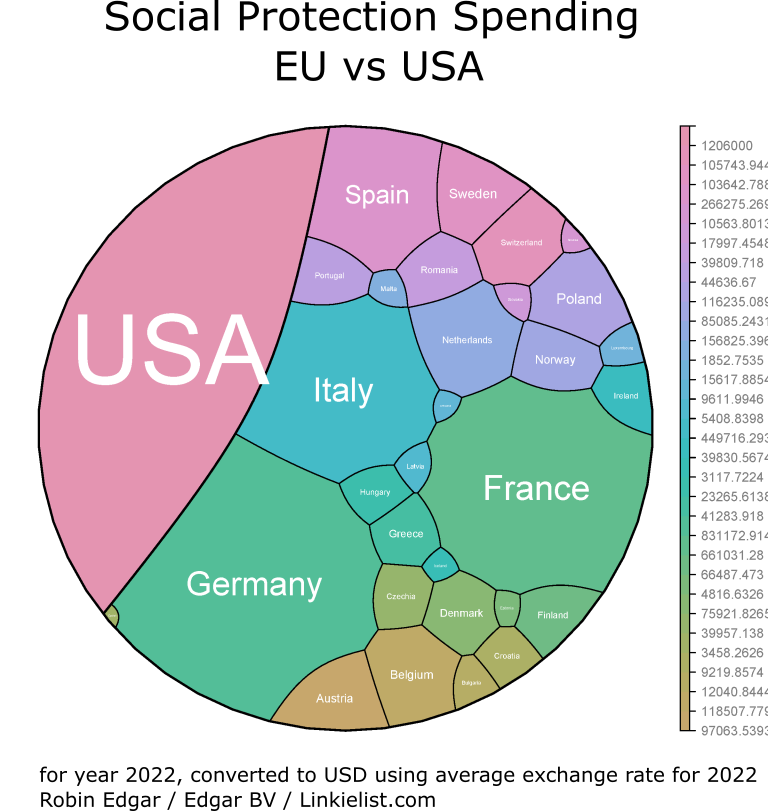

In 2022 the USA spent 1.2 billion dollars on Social Protection. The EU 3.46 billion dollars.

Note – this does not include the UK. Including the UK would make the USA look even worse than this.

Social spending EU 2022: Eurostat

Social spending US 2022: US / https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58592/html

Average exchange rate EUR to USD in 2022: https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/EUR-USD-spot-exchange-rates-history-2022.html

OECD social spending in 2022: OECD (2024), Social spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7497563b-en (Accessed on 13 March 2024)

Voronoi Treemap Generator / another Voronoi Treemap generator

As you can tell, the EU seems to care a lot more for it’s citizens.

The EU also believes in prevention. Delivering Official development assistance (ODA) is a way to prevent conflicts globally. The EU spends around EUR 50 billion per year on ODA, the US requested $10.5 billion in bolstering humanitarian assistance 2023. The EU is also set to spend around EUR 578 billion on climate spending in the period between 2021 – 2027, around 82.5 billion per year. The US around $2.3 billion in 2023. Climate change affects refugee streams, changing ecosystems and their economic attractiveness. It also makes working conditions harder for people in the defence industry:

The security threats of climate change

With the alarming acceleration of global warming and weather extremes across the globe, environmental issues have become more severe and climate change has become a defining issue of our time. Climate change causes complications for fresh water management and water scarcity, as well as health issues, biodiversity loss and demographic challenges. Other consequences like famine, drought and marine environmental degradation lead to loss of land and livelihood, and have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, and poor and vulnerable populations.

Climate change is also a threat multiplier that affects NATO security, operations and missions both in the Euro-Atlantic area and in the Alliance’s broader neighbourhood. It makes it harder for militaries to carry out their tasks. It also shapes the geopolitical environment, leading to instability and geostrategic competition and creating conditions that can be exploited by state and non-state actors that threaten or challenge the Alliance. Increasing surface temperatures, thawing permafrost, desertification, loss of sea ice and glaciers, and the opening up of shipping lanes may cause volatility in the security environment. As such, the High North is one of the epicentres of climate change.

Climate change affects the current and future operating environment, and the military will need to ensure its operational effectiveness in increasingly harsh conditions. Greater temperature extremes, sea level rise, significant changes in precipitation patterns and extreme weather events test the resilience of militaries and infrastructure. For example, increases in ambient temperatures coupled with changing air density (pressure altitude) can have a detrimental impact on fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft performance and air transport capability. Similarly, preventing the overheating of military aircraft, especially the sensitive electronic and airbase installations, requires an increased logistical effort and higher energy consumption. Many transport routes are located on coastal roads, which are particularly vulnerable to weather extremes. These are not only challenges to engineering and technology development, but must also be factored into operational planning scenarios.

Source: Environment, climate change and security | NATO

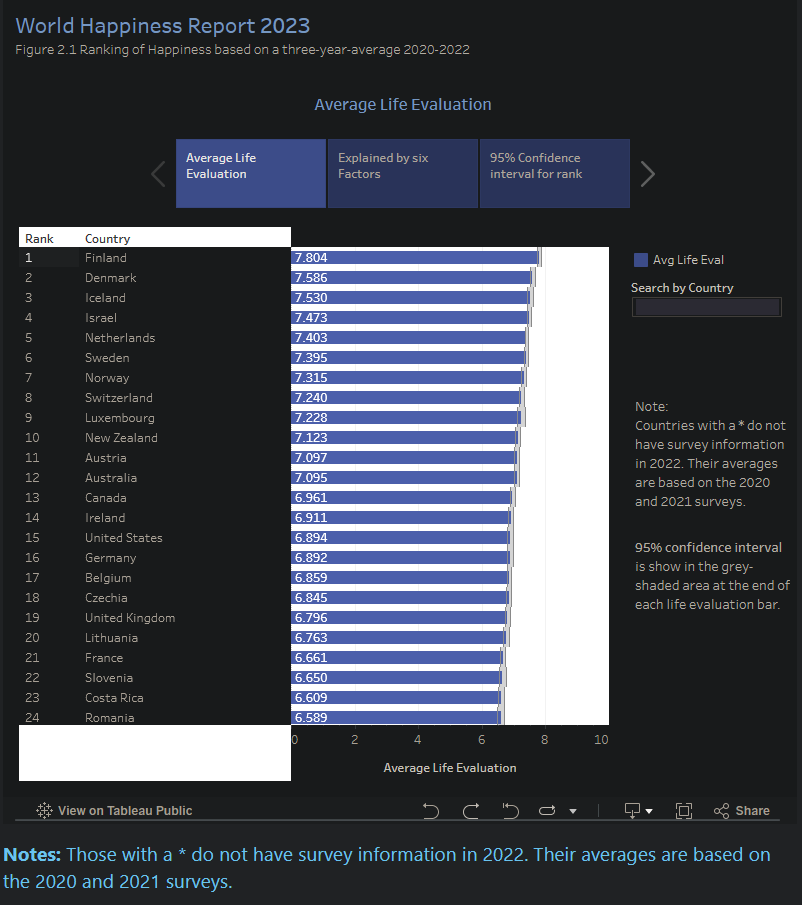

Happiness

The USA scores place 15, places 1 – 9 are all in the EU.

Source: World Happiness, Trust and Social Connections in Times of Crisis | World Happiness Report

Conclusion

The US does indeed spend more than the EU on its’ armed forces, but the amount ‘spent on NATO’ is not a true reflection. The US budget also includes homeland forces as well as the expeditionary ambitions of the USA. It also turns out that the USA thwarts attempts by Europe to form a common security and defence policy, both through their vocal stance against “duplication” by the EU of NATO forces and their strong arm tactics that force the EU to buy American to the detriment of the EU arms industry.

The US budget props up an arms based economy, to the detriment of the US population. US citizens notably less happy than EU citizens, most likely due to the relatively tiny amount that the US spends on social protections, relative to the EU countries.

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft