[…] Knowing the wave function of such a quantum system is a challenging task—this is also known as quantum state tomography or quantum tomography in short. With the standard approaches (based on the so-called projective operations), a full tomography requires large number of measurements that rapidly increases with the system’s complexity (dimensionality).

Previous experiments conducted with this approach by the research group showed that characterizing or measuring the high-dimensional quantum state of two entangled photons can take hours or even days. Moreover, the result’s quality is highly sensitive to noise and depends on the complexity of the experimental setup.

The projective measurement approach to quantum tomography can be thought of as looking at the shadows of a high-dimensional object projected on different walls from independent directions. All a researcher can see is the shadows, and from them, they can infer the shape (state) of the full object. For instance, in CT scan (computed tomography scan), the information of a 3D object can thus be reconstructed from a set of 2D images.

In classical optics, however, there is another way to reconstruct a 3D object. This is called digital holography, and is based on recording a single image, called interferogram, obtained by interfering the light scattered by the object with a reference light.

The team, led byEbrahim Karimi, Canada Research Chair in Structured Quantum Waves, co-director of uOttawa Nexus for Quantum Technologies (NexQT) research institute and associate professor in the Faculty of Science, extended this concept to the case of two photons.

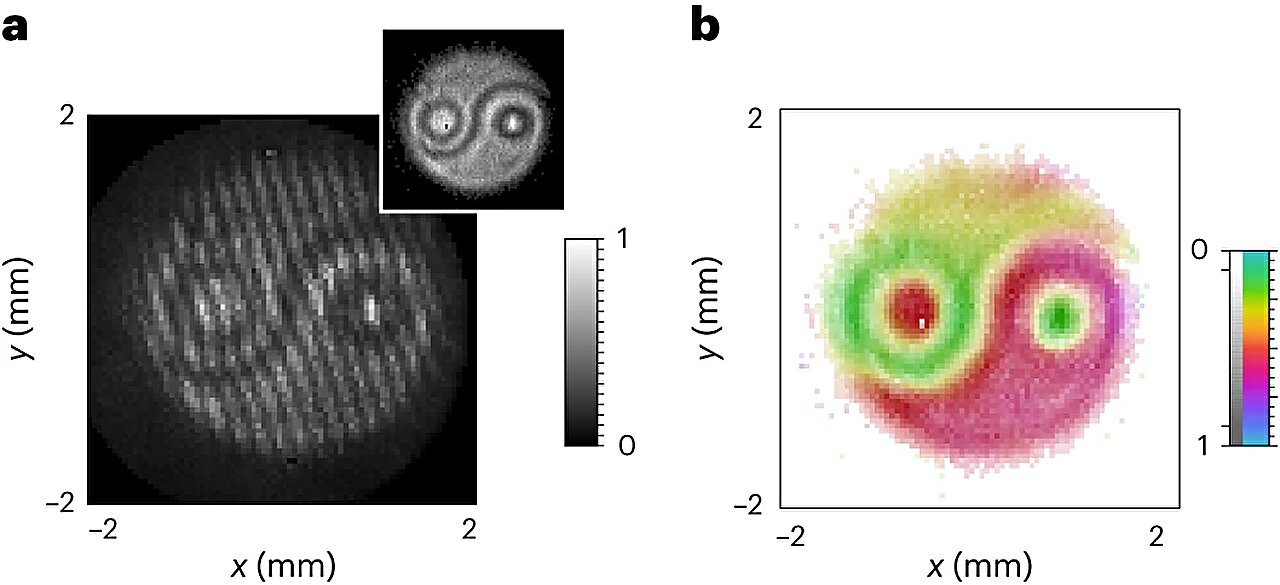

Reconstructing a biphoton state requires superimposing it with a presumably well-known quantum state, and then analyzing the spatial distribution of the positions where two photons arrive simultaneously. Imaging the simultaneous arrival of two photons is known as a coincidence image. These photons may come from the reference source or the unknown source. Quantum mechanics states that the source of the photons cannot be identified.

This results in an interference pattern that can be used to reconstruct the unknown wave function. This experiment was made possible by an advanced camera that records events with nanosecond resolution on each pixel.

Dr. Alessio D’Errico, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Ottawa and one of the co-authors of the paper, highlighted the immense advantages of this innovative approach, “This method is exponentially faster than previous techniques, requiring only minutes or seconds instead of days. Importantly, the detection time is not influenced by the system’s complexity—a solution to the long-standing scalability challenge in projective tomography.”

The impact of this research goes beyond just the academic community. It has the potential to accelerate quantum technology advancements, such as improving quantum state characterization, quantum communication, and developing new quantum imaging techniques.

The study “Interferometric imaging of amplitude and phase of spatial biphoton states” was published in Nature Photonics.

More information: Danilo Zia et al, Interferometric imaging of amplitude and phase of spatial biphoton states, Nature Photonics (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41566-023-01272-3

Source: Visualizing the mysterious dance: Quantum entanglement of photons captured in real-time

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft