[…] humans have sent over 15,000 satellites into orbit. Just over half are still functioning; the rest, after running out of fuel and ending their serviceable life, have either burned up in the atmosphere or are still orbiting the planet as useless hunks of metal.

[…]

That has created an aura of space junk around the planet, made up of 36,500 objects larger than 10 centimeters (3.94 inches) and a whopping 130 million fragments up to 1 centimeter (0.39 inches).

[…]

“Right now you can’t refuel a satellite on orbit,” says Daniel Faber, CEO of Orbit Fab. But his Colorado-based company wants to change that.

[..]

the lack of fuel creates a whole paradigm where people design their spacecraft missions around moving as little as possible.

“That means that we can’t have tow trucks in orbit to get rid of any debris that happens to be left. We can’t have repairs and maintenance

[…]

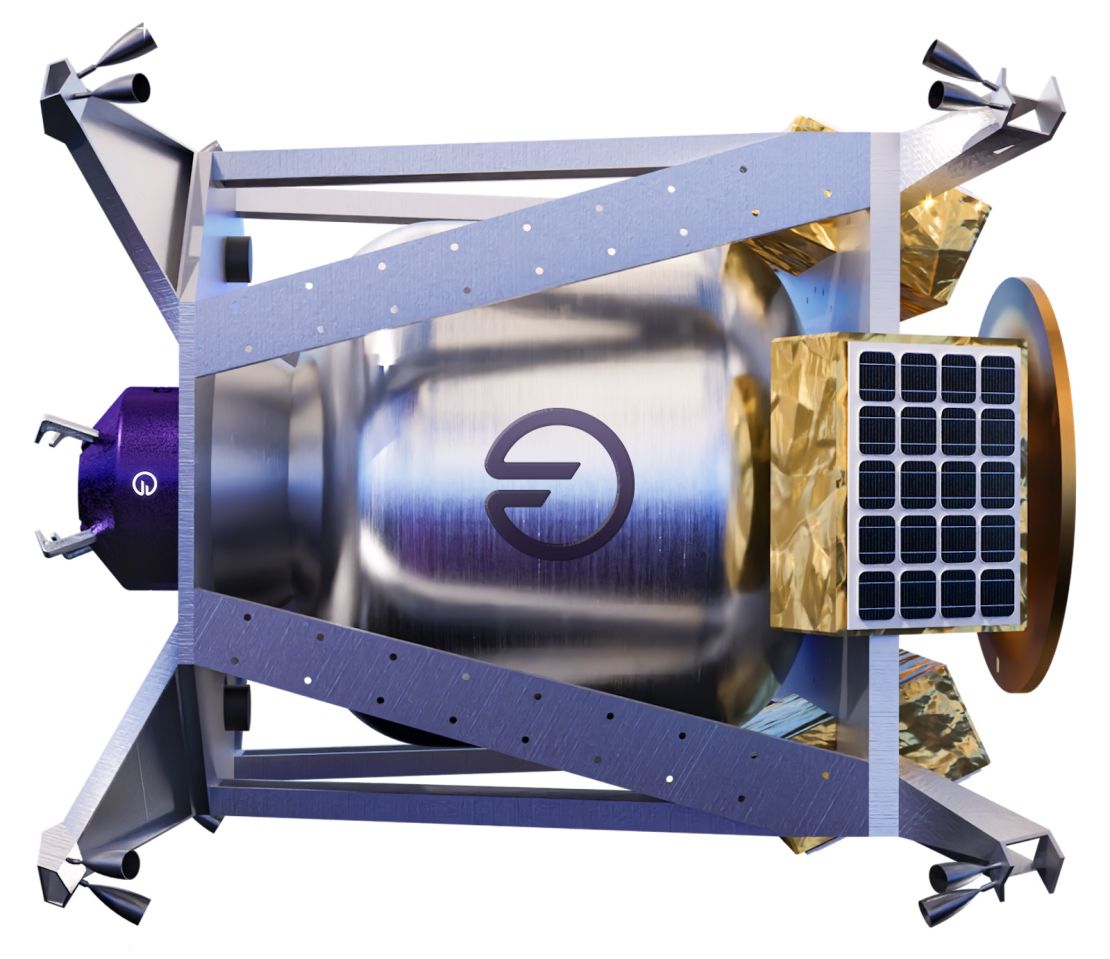

Orbit Fab has no plans to address the existing fleet of satellites. Instead, it wants to focus on those that have yet to launch, and equip them with a standardized port — called RAFTI, for Rapid Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface — which would dramatically simplify the refueling operation, keeping the price tag down.

“What we’re looking at doing is creating a low-cost architecture,” says Faber. “There’s no commercially available fuel port for refueling a satellite in orbit yet. For all the big aspirations we have about a bustling space economy, really, what we’re working on is the gas cap — we are a gas cap company.”

Orbit Fab, which advertizes itself with the tagline “gas stations in space,” is working on a system that includes the fuel port, refueling shuttles — which would deliver the fuel to a satellite in need — and refueling tankers, or orbital gas stations, which the shuttles could pick up the fuel from. It has advertized a price of $20 million for on-orbit delivery of hydrazine, the most common satellite propellant.

In 2018, the company launched two testbeds to the International Space Station to test the interfaces, the pumps and the plumbing. In 2021 it launched Tanker-001 Tenzing, a fuel depot demonstrator that informed the design of the current hardware.

The next launch is now scheduled for 2024. “We are delivering fuel in geostationary orbit for a mission that is being undertaken by the Air Force Research Lab,” says Faber. “At the moment, they’re treating it as a demonstration, but it’s getting a lot of interest from across the US government, from people that realize the value of refueling.”

Orbit Fab’s first private customer will be Astroscale, a Japanese satellite servicing company that has developed the first satellite designed for refueling. Called LEXI, it will mount RAFTI ports and is currently scheduled to launch in 2026.

[…]

He adds that once the pattern of sending and delivering fuel in orbit is established, the next step is to start making the fuel there. “In 10 or 15 years, we’d like to be building refineries in orbit,” he says, “processing material that is launched from the ground into a range of chemicals that people want to buy: air and water for commercial space stations, 3D printer feedstock minerals to grow plants. We want to be the industrial chemical supplier to the emerging commercial space industry.”

Source: Orbit Fab wants to create ‘gas stations in space’ | CNN

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft